More from the Spring/Summer 2015 issue of Ribbons, the Tanka Society of America Journal, and its theme of tanka based on novels.

For those willing to let themselves feel it, any story leaves behind something at the center, other times at the edge of perception, and poetry’s work is in part, to take up that residue and remnant.

For those willing to let themselves feel it, any story leaves behind something at the center, other times at the edge of perception, and poetry’s work is in part, to take up that residue and remnant.

In her tanka, her own identification with the protagonist of a novel by Nina Schuyler, Amelia Fielden courageously writes:

The Translator: / how much like Hanne’s story/ might mine have been/ had I chosen to stay/ with a Japanese lover

I’m impressed by Fielden’s honesty; her life experience means that her tanka are never dull. It’s clear that not choosing to stay with her Japanese lover was a pivotal experience in her life. One of the things I like about tanka in general is the opportunity to let down your hair, let others know who you are, share the richness or poverty, physical or emotional, of your life. Tanka readers are listeners. You know there will be a listener.

I’m impressed by Fielden’s honesty; her life experience means that her tanka are never dull. It’s clear that not choosing to stay with her Japanese lover was a pivotal experience in her life. One of the things I like about tanka in general is the opportunity to let down your hair, let others know who you are, share the richness or poverty, physical or emotional, of your life. Tanka readers are listeners. You know there will be a listener.

That ‘might’ may indicate simple nostalgia, simple memory, or regret. I like its open endedness. This poem could be about a secret she has been longing to share; I can imagine her intensity as she was reading The Translator, how well she must have understood Hanne’s emotions and her struggles. In five lines Amelia Fielding has said all that.

Linda Jeannette Ward goes into the psychological center of one of the characters by writing:

at the thrift shop/ Lady Chatterley’s Lover/ is falling to pieces/ I see she contains herself/ no better than I

Ward’s three choices of phrase, ‘falling to pieces’ and ‘she contains herself’ and ‘no better than I’ puts you right inside her mind. Lady Chatterley, thanks to D.H. Lawrence, has become a part of the poet; ‘no better than I’ shows a vulnerability, the kind of thing that makes us worry about ourselves. We bring ourselves to a ‘station’ in life, but know there are darknesses within ourselves that might one day make us crash, or simply react without thought of consequence.

Ward’s three choices of phrase, ‘falling to pieces’ and ‘she contains herself’ and ‘no better than I’ puts you right inside her mind. Lady Chatterley, thanks to D.H. Lawrence, has become a part of the poet; ‘no better than I’ shows a vulnerability, the kind of thing that makes us worry about ourselves. We bring ourselves to a ‘station’ in life, but know there are darknesses within ourselves that might one day make us crash, or simply react without thought of consequence.

You can imagine yourself standing in the store with her, surrounded by clothes and household items. It smells a bit musty. She has an ironic look on her face, yet you sense that what she is feeling is deeper than irony. You want to be able to ask if she needs a shoulder to lean on, if she’s okay. And then she will laugh and you’ll go for coffee.

the Guilt/ indulging in this hearty/ Irish boiled dinner/ beneath its savor, a taste/ of Angela’s Ashes

the Guilt/ indulging in this hearty/ Irish boiled dinner/ beneath its savor, a taste/ of Angela’s Ashes

Autumn Noelle Hall brings back the guilt (oh that wonderful capital ‘G’!) we try to suppress when we feel particularly replete; it brings back our mother saying ‘Think of all the starving children in China”, and the images of famine and war we have just seen on the news or passed over in the newspaper. How can we eat after all that. But we do, we carry on as if such terrible things don’t happen to real people in the world.

The inspired pairing of ‘…hearty/ Irish boiled dinner/’ with the word ‘Ashes’ leaves you with the sensation of ashes in your mouth. It’s a visceral reaction; the poem leaves you uneasy. Frank McCourt makes us feel uneasy. Fiction can hit truth close to the bone. In the few words of a tanka, Hall reminds us of the history of the Irish people, contemporary and in the not so recent past. It’s a reminder that it’s in the Irish character that their history is alive for them every day of their lives.

“a rose in my hair/ like the Andalusian girls…/ yes I will yes”/ should I change my name to Molly

Semi-quoting, lifting words from the glorious ending of James Joyce’s Ulysses and using them in a tanka… I take my hat off to you Kath Abela Wilson. It’s genius!

Semi-quoting, lifting words from the glorious ending of James Joyce’s Ulysses and using them in a tanka… I take my hat off to you Kath Abela Wilson. It’s genius!

Readers tend to become engrossed in the lives of Leopold and Molly, empathising with them over the loss of their son, their issues, their friendships, their passions. We ache to be brave enough to live as fully as they do.

But if Leopold Bloom functions as a sort of Everyman, then Molly functions as every woman, a strong woman, an ardent woman who does not want to let life pass her by. There is more than one reason for a woman yearning after ‘Mollyness’; the two last lines capture that yearning.

In creating new poetry from the writing of another, the poet identifies in his/her personal way with the original author, and the new poem gives the original work an indefinable immediacy. Poets sense an underwritten suggestion, think ‘maybe I’ll go back to that novel too’. There, tanka writers, your work is done!

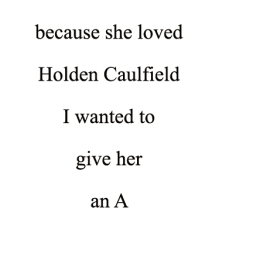

LeRoy Gorman has been a longtime supporter of visual poems. As editor of the Haiku Canada Review, he has accepted many such poems, aware of their visual impact and how a visual arrangement can affect the meaning of a poem. Here he arranges the lines into an upside-down A, but the lines step down carefully and deliberately to the possible result of a decision he has to make.

LeRoy Gorman has been a longtime supporter of visual poems. As editor of the Haiku Canada Review, he has accepted many such poems, aware of their visual impact and how a visual arrangement can affect the meaning of a poem. Here he arranges the lines into an upside-down A, but the lines step down carefully and deliberately to the possible result of a decision he has to make.

It’s amazing how quickly participants begin to move as one, like a flock of starlings; there’s a movement, suddenly the poem can go one way, and in the next verse, go somewhere else, all the poets interacting. Everyone is on the same side in this game, everyone wants to win, and the prize is a completed renku. Some writers think and work quietly, others get excited, competitive and rowdy while the parts of the renku are busy forming the whole. At Versefest it was no different― there we were all scrambling to write the next verse.

It’s amazing how quickly participants begin to move as one, like a flock of starlings; there’s a movement, suddenly the poem can go one way, and in the next verse, go somewhere else, all the poets interacting. Everyone is on the same side in this game, everyone wants to win, and the prize is a completed renku. Some writers think and work quietly, others get excited, competitive and rowdy while the parts of the renku are busy forming the whole. At Versefest it was no different― there we were all scrambling to write the next verse.

This little one was with her parents playing outside the Museum in Shanghai one evening. With her red shoes that lit up when she walked, and a good luck charm on a cord around her neck, this came to mind:

This little one was with her parents playing outside the Museum in Shanghai one evening. With her red shoes that lit up when she walked, and a good luck charm on a cord around her neck, this came to mind: