It’s been seven months since I came back from Newfoundland and Nova Scotia, and those months have been busy. I’ve been writing, and am pleased and proud to be one of seven (out of two hundred submissions) on the shortlist in the 2017 Malahat Long Poem Contest with my series of lyric poems about Fogo Island, Newfoundland. I didn’t win, but have been sending those poems out as a chapbook submission, and maybe, just maybe, have had a hint of a chance with one publisher.

I love designing the covers of my books, collaborating with the authors so that they are completely happy with their books. Here are the books catkin press has published in the past seven months: First, Firefly in the Room by Grant D. Savage.

Cover photograph: Grant D. Savage

This unusual collection of erotic haiku by Grant Savage, an excellent haiku poet. His luscious photography was perfect for this theme in his use of colour and composition. And the haiku are astute and sassy.

The two next publications were compilations of haibun with tanka. The first was Hans Jongmann’s Swooning, a manuscript that was so good and so unusual in its narrative of love and being young, has a central mystery, that I just had to publish it. His wife Farida wrote a prose section which set things up beautifully. The reader is captivated, held to the last page.

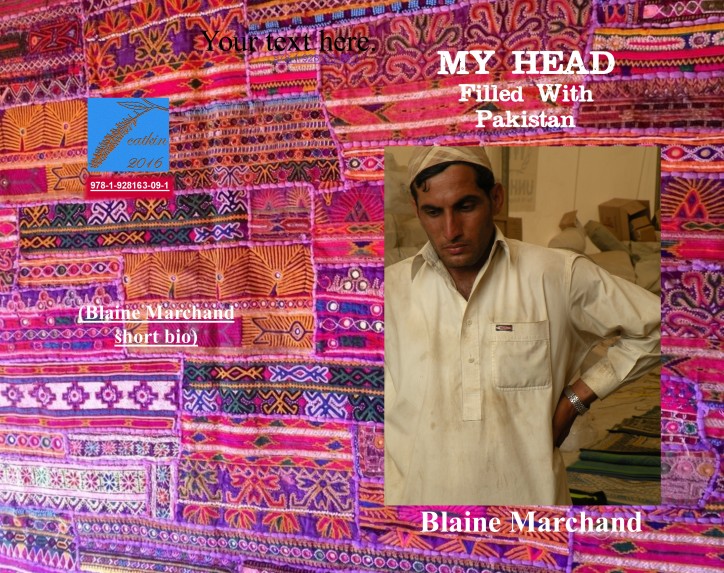

The next venture was a chapbook of poems, My Head Full of Pakistan, about Blaine Marchand’s deep love of the country where he worked with CIDA. Blaine was with me in every step of publication, from editing (and there was very little) to layout, to cover background and images, including choosing textured papers for the cover and for the interior pages, which reflected the textiles of that country. This is the cover in an early stage of design.

The next venture was a chapbook of poems, My Head Full of Pakistan, about Blaine Marchand’s deep love of the country where he worked with CIDA. Blaine was with me in every step of publication, from editing (and there was very little) to layout, to cover background and images, including choosing textured papers for the cover and for the interior pages, which reflected the textiles of that country. This is the cover in an early stage of design.

Blaine’s photograph is featured on this cover. There are several more inside the chapbook that serve to enhance and illustrate Blaine’s lyric poems. These are poems that give you a slice of Pakistan written by someone who loves that country and who is known for the depth and insights in his writing.

Blaine’s photograph is featured on this cover. There are several more inside the chapbook that serve to enhance and illustrate Blaine’s lyric poems. These are poems that give you a slice of Pakistan written by someone who loves that country and who is known for the depth and insights in his writing.

Then another haiku/ tanka/ haibun writer sent me a memoir called She Don’t Mean a Thing If She ain’t Got That Swing that intrigued and amazed me. Guy Simser of Ottawa focused on the love of his life, wife Jan, and on their travels, on the music and activities they shared for so many years. His writing was so rich in expression, description, detail and humour. What could I do except say I’d publish it.

Again the author was particular about the papers used for text and cover, and his choice of sensuous paper for the text meant that the many fascinating photographs printed perfectly in colour. This is a beautiful object as well as a well thought-out book.

Again the author was particular about the papers used for text and cover, and his choice of sensuous paper for the text meant that the many fascinating photographs printed perfectly in colour. This is a beautiful object as well as a well thought-out book.

In February we launched three books at Pressed, for Grant, Guy and Blaine, and what a dynamic set of presentations that was!

In the new year, Hans said he had a couple (a couple…!) more manuscripts. He has a reputation in the Japanese-form world for his sterling poems, so first we published Below the Frostline, which is completely haiku. The second, Shift Change, was another variation on memoir that focused on travel, bicycling, and work experiences in various places. His writing has honesty and colour. Each poem is just right. We argued over editing as we always have, but he is a wise writer and makes the right choices.

When Haiku Canada held its conference in Whitehorse last year, it happened to be Mystery Month in the Yukon. With that theme in mind, Haiku Canada members submitted ‘crime’ ku, a selection of which was printed on file cards in a clear large font and displayed with kindred books in a case in the library/museum foyer. The library asked whether there would be a book, and so Kathy Munro, haikuist, and Jessica Simon, crime writer, edited a thoughtful, humorous, delightful collection of Killer Ku. I loved working with them; I appreciated their enthusiasm and their fine insistence of particulars. They came up with the perfect headings for the sections, such as Breaking and Entering, Cannibalism, and Cell Blocks. Their inspired early layout and concise editing add so much to this very different collection which can be enjoyed, not only by haiku enthusiasts, but by anyone who picks it up.

When Haiku Canada held its conference in Whitehorse last year, it happened to be Mystery Month in the Yukon. With that theme in mind, Haiku Canada members submitted ‘crime’ ku, a selection of which was printed on file cards in a clear large font and displayed with kindred books in a case in the library/museum foyer. The library asked whether there would be a book, and so Kathy Munro, haikuist, and Jessica Simon, crime writer, edited a thoughtful, humorous, delightful collection of Killer Ku. I loved working with them; I appreciated their enthusiasm and their fine insistence of particulars. They came up with the perfect headings for the sections, such as Breaking and Entering, Cannibalism, and Cell Blocks. Their inspired early layout and concise editing add so much to this very different collection which can be enjoyed, not only by haiku enthusiasts, but by anyone who picks it up.

Anna Vakar is a long-time haiku poet who has spent her years in the haiku life learning what haiku is, what it could be. Vicki McCullough met Anna Vakar and realized that this poet needed to be better known and needed to have a book of her work. Vicki has done an amazing job writing introductions to both Anna’s life and her haiku path. Anna Vakar is a strong poet who has the habit of writing comments on the pages of any anthologies or haiku collections she acquires. The book includes a list of the kind of comments Anna writes beside and around the poems. A couple of photographs show pages of this perceptive self-teaching marginalia. Vicki is an editor who insists on academic excellence. She and Ms Vakar have produced the finest kind of haiku book, one that shows a haiku poet’s path while teaching about this form.

Anna Vakar is a long-time haiku poet who has spent her years in the haiku life learning what haiku is, what it could be. Vicki McCullough met Anna Vakar and realized that this poet needed to be better known and needed to have a book of her work. Vicki has done an amazing job writing introductions to both Anna’s life and her haiku path. Anna Vakar is a strong poet who has the habit of writing comments on the pages of any anthologies or haiku collections she acquires. The book includes a list of the kind of comments Anna writes beside and around the poems. A couple of photographs show pages of this perceptive self-teaching marginalia. Vicki is an editor who insists on academic excellence. She and Ms Vakar have produced the finest kind of haiku book, one that shows a haiku poet’s path while teaching about this form.

During these months I was co-editor, with Marco Fraticelli of Haiku Canada’s 40th members’ anthology, which is being published by Ekstasis Press in British Columbia. It is dedicated to one of the founders of the society, Eric Amann, who passed away last fall. The anthology is unusual as it isn’t just a haiku collection, but rather a gathering of haiku experiences, memories, stories of one’s first haiku publication, or how one came to haiku. Each member had one page which could be comprised of just haiku or part prose, even haibun.

During these months I was co-editor, with Marco Fraticelli of Haiku Canada’s 40th members’ anthology, which is being published by Ekstasis Press in British Columbia. It is dedicated to one of the founders of the society, Eric Amann, who passed away last fall. The anthology is unusual as it isn’t just a haiku collection, but rather a gathering of haiku experiences, memories, stories of one’s first haiku publication, or how one came to haiku. Each member had one page which could be comprised of just haiku or part prose, even haibun.

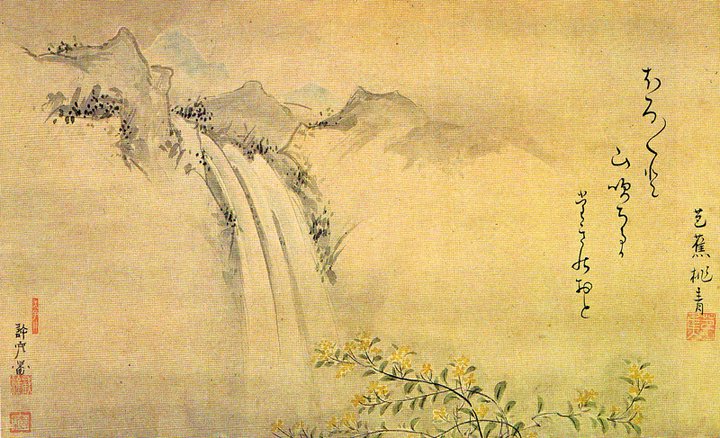

Its title, Wordless, is from a little book Amann wrote early on, which influenced many haikuists. Marco and I learned a lot from co-editing this collection, especially about how accommodating and patient an anthology publisher can be. Richard Olafson of Ekstasis Editions is a dream to work with. I’m sure we were a nightmare to him with our hundreds of edits. We are so pleased that the cover will feature a painting by Aili Kurtis of Perth. Richard let me design the cover, at least in its first phases. This is an early draft:

Then came a great event! Managing editor Mike Montreuil of Éditions des petits nuages said the press would publish MY haiku collection! AND would be happy to let me design its cover. Well, paradise for me! The book is dedicated to musician/philosopher Oliver Shroer, whom I knew, but would like to have known better for how he lived his life, the music he took risks with. He was one of those special people. When he was diagnosed with leukemia, he walked the Camino, and played in 25 churches along the way. Much of his playing, on stage and in those churches, even in hospital during the later stages of the disease, can be seen in videos on the net. When I met the 6’3′ or 4′ Oliver at a festival in Owen Sound, he was wearing a bowler hat. I had kept a file of an image Ellen Drennan had put on facebook, and she let me use it as the background. Her image is full of energy and light, perfect for an ‘Oliver’ book. The haiku are not about Oliver, except for a few; the poems range, I hope, between a very few ‘not-too-bad’ haiku to several that will be judged ridiculous, and everything in between. I had three very good editors beside Mike Montreuil: Philomene Kocher of Kingston, Marco Fraticelli and Grant Savage of Ottawa, but they can’t be blamed for what I finally included.

Then came a great event! Managing editor Mike Montreuil of Éditions des petits nuages said the press would publish MY haiku collection! AND would be happy to let me design its cover. Well, paradise for me! The book is dedicated to musician/philosopher Oliver Shroer, whom I knew, but would like to have known better for how he lived his life, the music he took risks with. He was one of those special people. When he was diagnosed with leukemia, he walked the Camino, and played in 25 churches along the way. Much of his playing, on stage and in those churches, even in hospital during the later stages of the disease, can be seen in videos on the net. When I met the 6’3′ or 4′ Oliver at a festival in Owen Sound, he was wearing a bowler hat. I had kept a file of an image Ellen Drennan had put on facebook, and she let me use it as the background. Her image is full of energy and light, perfect for an ‘Oliver’ book. The haiku are not about Oliver, except for a few; the poems range, I hope, between a very few ‘not-too-bad’ haiku to several that will be judged ridiculous, and everything in between. I had three very good editors beside Mike Montreuil: Philomene Kocher of Kingston, Marco Fraticelli and Grant Savage of Ottawa, but they can’t be blamed for what I finally included.

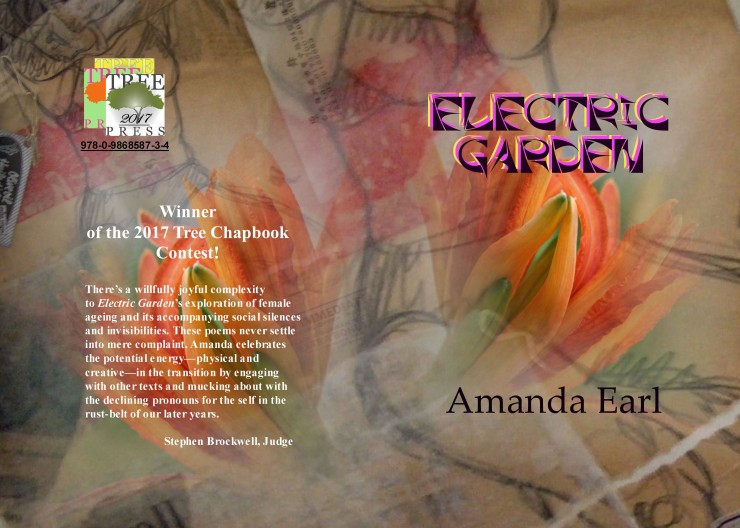

One of the last cover designs has been for the winning Tree Chapbook manuscript for 2017, Amanda Earl’s Electric Garden. The judge, Steven Brockwell, took the time he needed to choose a winner from so many fine submissions, but is definite about the talent of Ms Earl. Her poems are tight and energetic and honest with a superlative use of language. She sent me an image of a lily I might want to use, and agreed to let me incorporate it into a collage. I think we’re both pleased with that collaboration. Here it is:

One of the last cover designs has been for the winning Tree Chapbook manuscript for 2017, Amanda Earl’s Electric Garden. The judge, Steven Brockwell, took the time he needed to choose a winner from so many fine submissions, but is definite about the talent of Ms Earl. Her poems are tight and energetic and honest with a superlative use of language. She sent me an image of a lily I might want to use, and agreed to let me incorporate it into a collage. I think we’re both pleased with that collaboration. Here it is:

And that will almost do it. I produced a tiny personal chapbook of a long poem, Body of Light, and will publish one more collection before the end of June, for Grant Savage.

And that will almost do it. I produced a tiny personal chapbook of a long poem, Body of Light, and will publish one more collection before the end of June, for Grant Savage.

That’s been my publishing year. These titles join the previous list of publications, including Singing in the Silo by Philomene Kocher, and Drifting by Marco Fraticelli, as well as others. It’s one of the reasons I didn’t turn up for a lot of poetry events. I won’t have such a heavy schedule ever again, but I’m glad every one of these is a catkin press production, and I am so proud of the editors and authors. What a great crew!

That’s been my publishing year. These titles join the previous list of publications, including Singing in the Silo by Philomene Kocher, and Drifting by Marco Fraticelli, as well as others. It’s one of the reasons I didn’t turn up for a lot of poetry events. I won’t have such a heavy schedule ever again, but I’m glad every one of these is a catkin press production, and I am so proud of the editors and authors. What a great crew!

Most of the books will be available at the Haiku Canda Weekend in Mississauga, May 19 – 21 at The University of Toronto at Mississauga, and at the Small Press Book Fair in June. This adventure of being a small press publisher is turning out to be quite the journey. I wouldn’t have missed it for the world.

Oops! I forgot something… Pearl Pirie’s Phafours Press published a chapbook of my gendai one-liners. That means a lot. Many thanks, Pearl for sometimes seeing the world and language the way I sometimes do… I apologize that this is only an approximation of the cover with art by Judith Copithorne. I’ve run out of copies, so I can’t photograph it. But I love it!

When I began catkin press, I wanted fiercely to start with publishing poetry by Marco Fraticelli. Any poetry by Fraticelli, and I was sure he was hiding a manuscript or two, or ideas for a manuscript or two, so I asked him. Turned out there was an idea he had been thinking about and working on for a long time. Not the haiku or lyric poetry he was known for, something else: haibun based on some old papers he had found in an abandoned house in the Eastern Townships over 30 years ago.

When I began catkin press, I wanted fiercely to start with publishing poetry by Marco Fraticelli. Any poetry by Fraticelli, and I was sure he was hiding a manuscript or two, or ideas for a manuscript or two, so I asked him. Turned out there was an idea he had been thinking about and working on for a long time. Not the haiku or lyric poetry he was known for, something else: haibun based on some old papers he had found in an abandoned house in the Eastern Townships over 30 years ago.